In the era of globalized tourism, Bali—the tropical jewel of Indonesia—has become a symbol of a problem that goes beyond economic or environmental concerns: the loss of cultural meaning. This island, once a spiritual and aesthetic sanctuary of Balinese tradition, now struggles to survive under the pressure of mass tourism, a phenomenon that not only consumes its natural resources but also alarmingly erodes its cultural identity. The irony is that this transformation comes at the hands of human beings, who, since Aristotelian times, have been defined as “rational animals.”

Aristotle conceived of man as the only being capable of reasoning, deliberating, and seeking the common good. However, what we see today in Bali seems to contradict this premise. If human beings have the capacity to think and reflect, why do they behave like irrational animals that prey on, impose upon, and destroy what does not belong to them? This contradiction leads to an even more unsettling question: has modern man lost the compass of his traditional values?

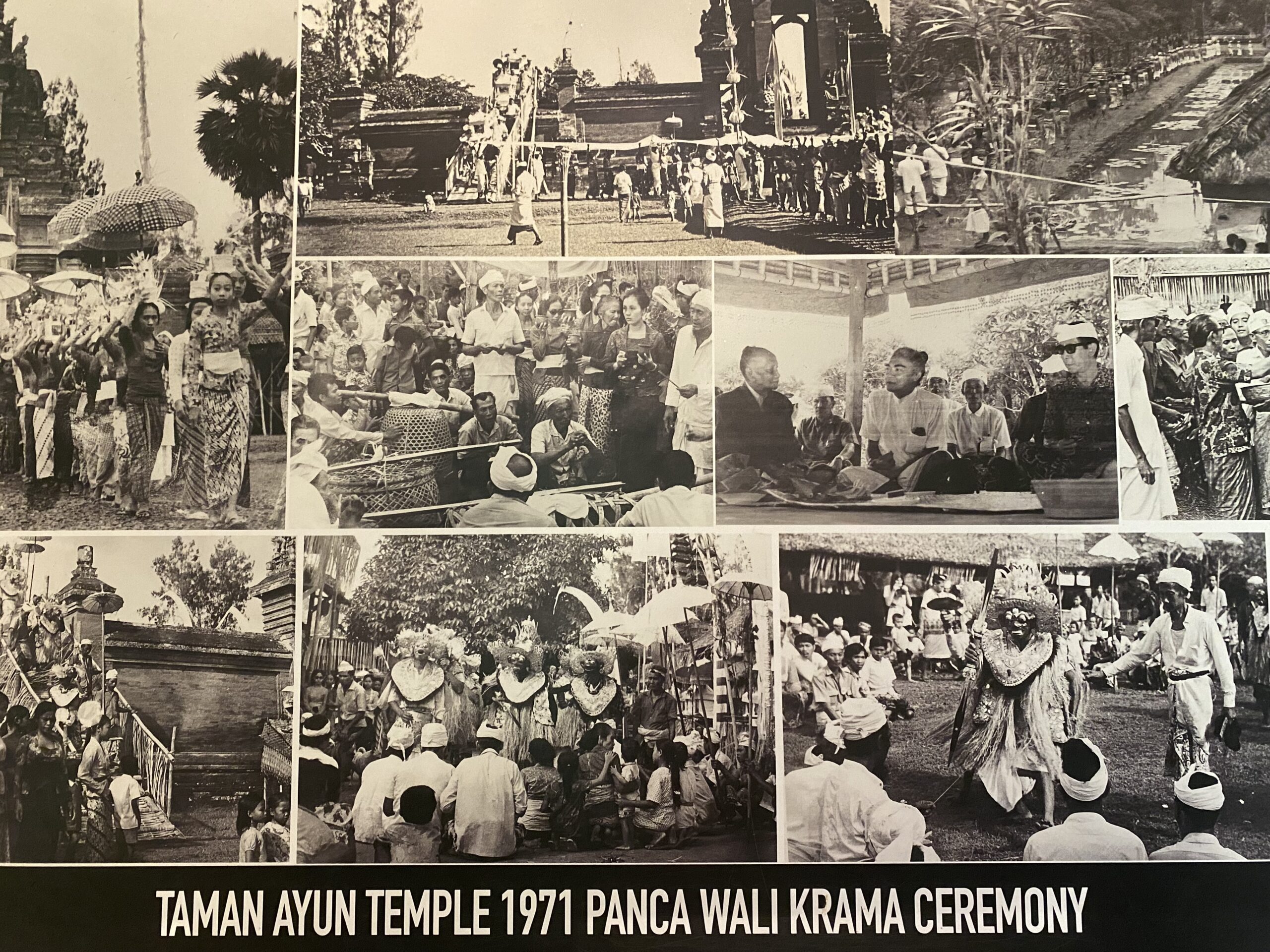

The massive arrival of foreigners in Bali has turned the sacred into a spectacle. Ritual dances that once had spiritual significance are now presented as tourist attractions, often to visitors who neither understand nor value their symbolism. Local cuisine has been displaced by international menus adapted to foreign tastes, and beaches, once natural sanctuaries, have been altered by infrastructures catering more to tourist comfort than to respect for the ecosystem. The case of Kelingking Beach in Nusa Penida is emblematic: building a tourist elevator down the cliff to the coast threatens not only the aesthetics of the landscape but also the balance of endemic flora and fauna.

The root of this situation seems to lie in a modern form of “tourism nihilism,” where the visitor, stripped of transcendent values, reduces the travel experience to selfish and fleeting consumption. The notion of the other is lost, as is the sense of a place as a living entity with history and soul. The tourist, blinded by the promise of an “exotic paradise,” imposes without reflection, and in the eagerness to “live experiences,” forgets the need to respect them.

Against this backdrop, the reality of Indonesian cities like Pekanbaru stands out with hope. Not being a tourist epicenter, this city has managed to preserve a strong cultural identity, rooted in Malay traditions. Here, poems, ritual weddings, the custom of chewing betel, traditional clothing, nicknames like Mr. Long or Mr. Ngah, funeral ceremonies, customary titles, and even laws based on ancestral rights remain alive—not as mere folklore for the camera, but as an organic part of daily life. And together with these customs, essential values also endure: humility, gratitude, affection, and hospitality.

Shouldn’t the modern tourist learn from this example? Are we not, as Aristotle said, beings with the capacity to learn, to contemplate, to choose what is good? If so, then traveling should not be an invasive act, but rather an exercise in recognizing the other—a philosophical, even spiritual, act.

Today, more than ever, Indonesia needs conscientious tourists: men and women who travel not to impose, but to learn; who do not seek to bring their own world to Bali, but to encounter the Balinese world; who do not destroy for the sake of a photograph, but instead contemplate in order to respect.

Because in the end, the real journey is not only geographic—it is also an inner journey into the human being. And perhaps, just perhaps, if we begin to travel with a conscious mindset, the world we visit will not be destroyed, but shared with dignity.

And with that, humanity will cease to act like an irrational animal… and return to being what it has always been called to be: human.

0 Thoughts on Bali